Our Miss Brooke

In his book The Secret Life of Bob Hope (Barricade Books, 1993), Arthur Marx quotes Steve Allen as having once said, “Bob Hope is never as popular as when there is a war going on. I don’t mean that to be a wisecrack so much as a plain statement of truth.” Most likely, Hope would have agreed with him. Throughout my years on his staff, he strove to maintain his image as “America’s Entertainer to the Troops” and was on constant alert for an opportunity to fly somewhere and stage a show for the military.

During the years between Vietnam and the war in the Middle East, he decided to entertain the U.S. forces right here at home. At the start of the 1979 season, we taped a special aboard the helicopter carrier Iwo Jima docked in New York harbor. The show featured guest stars Don Knotts — as a nearsighted whirlybird jockey — a hot new disco group called The Village People, and, the then-current star of Annie singing “I Don’t Need Anyone But You” to Hope’s Daddy Warbucks, a freckled, fourteen-year-old Sarah Jessica Parker. (Occasionally, she plays the clip on Letterman.) The only downside of the show was a gust of wind that blew one of our $40,000 cameras off the flight deck into the Hudson River.

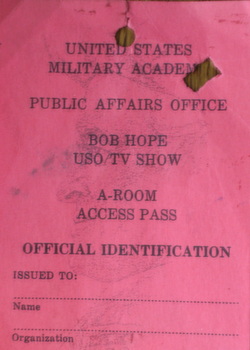

The military-themed show was a hit with both viewers and critics, so the following year our producer, Jim Lipton — who also produced our China special and now hosts Inside the Actors Studio on Bravo — proposed a trilogy of specials that would emanate from the nation’s military academies. The shows turned out to fill the bill perfectly — they offered plenty of flag waving, got Hope into uniform, and, to the great relief of the writers, involved virtually no risk to life and limb. We hoped the peace would last forever.

At West Point, which we visited in the spring of 1981, we dressed Hope in the black cape and orange vest of the Academy’s legendary “Airborne Man” and dropped him — with a little help from a stunt double — from a hovering Huey helicopter into a stadium packed to the bleachers with cheering plebes and their families.

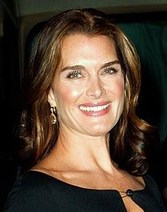

The Army had recently admitted its first female cadet so we had guest stars Brooke Shields and Marie Osmond in uniform faster than Shannon Faulkner would reject the Citadel’s fourteen years later. The new arrivals discover that they’ve somehow been assigned quarters with a male.

(Hope enters in uniform and carrying a duffle bag,)

HOPE: Howdy, fellas.

MARIE: Fellas? Can’t you see that we’re girls?

HOPE: Yeah, but I wasn’t gonna mention it if you didn’t. My name’s Luke Festus, and it looks like we’re roommates.

BROOKE: Are you sure you have the right room? There must be some mistake.

HOPE: I doubt it. The Army never makes mistakes.

Hope’s line, of course, drew a deafening cheer. They may be future officers, but first-year plebes occupy rungs on the military ladder barely above meter maids and relish the opportunity to poke fun at their brass-laden faculty.

BROOKE: I’m sorry, Luke, but this would never work. We could walk in on one another while showering.

HOPE: I guess that’s just the chance I’ll have to take.

MARIE: Be reasonable. You wouldn’t want to have stockings hanging all over the place to dry, would you?

HOPE: Hey, no problem. If it bothers you, I’ll hang my stockings someplace else.

The fresh recruits settle in. Hope wants to change into his “jammies,” but is embarrassed to disrobe in front of the girls. They offer to hold up a blanket, shielding him. With Brooke and Marie at either end of the extended blanket, he drapes articles of clothing on it. First a girdle, then a garter belt, then a pair of Madras Jockey shorts.

BROOKE: Should we look?

MARIE: Nah. It’s too close to lunch.

This line gets the biggest laugh in the show, and Hope could be heard mumbling to Marie, “How did you get that line?” He didn’t mind guests getting laughs but preferred being visible when they did. As it turns out, Luke works on a nearby farm and has been trying to sneak into the Point for years. The cadet commander (Glen Campbell) hustles the intruder off, but not before making sure the two newcomers know where his quarters are. Coed dorms had provided us fertile diggings for years, and this sketch was no exception.

This academy special marked Brooke Shields’ first appearances on our show. During the ten seasons that would follow, she would do thirteen more, a record. Loni Anderson was second with six or seven; we lost count. Under the watchful eye of her quintessential stage mother, Teri, whom writer Charlie Isaacs once accused of “carrying Brooke’s virginity in her purse,” she arrived lugging some heavy child-star baggage that included a nude scene in a movie called Pretty Baby as well as another au naturel performance in a picture called The Blue Lagoon.

Hope took an immediate liking to Brooke, and she to him, showering him with the affection one would bestow on a kindly grandfather. Hope may have been a father figure, too, as her parents had been long divorced. From her first appearance, Hope took Brooke under his wing, teaching her the basics of sketch comedy — timing, delivery, entrances and exits — techniques which seem effortless, but must be learned, nonetheless.

For her part, Brooke obviously enjoyed performing on the show, was eager to learn and, as would be expected, improved as time went on playing roles ranging from Becky Thatcher opposite Hope’s Tom Sawyer (at the World’s Fair in New Orleans where she forgot she was wearing a remote microphone transmitter, jumped into the Olympic diving pool, and almost demonstrated GE’s “We Bring Good Things to Light” slogan) to a Showboat singer opposite Placido Domingo’s Gaylord Ravenal — “We could make believe...” to Princess Diana. The Hope specials kept her acting career afloat during her Princeton University, pre-Andre Agassi period. She made one movie, Brenda Starr,that bombed.

But as often happens in Hollywood, Brooke was stricken by a sudden case of selective amnesia when, in September 1996, she told an interviewer for the Los Angeles Times while discussing successful guest appearances on Friends, that “[Comedy] is something that I’ve never professionally explored and I’ve never had the opportunity or encouragement.” There was a logical explanation for her forgetfulness. By the mid-nineties, Hope was considered passé, and generations removed from the then-current TV comedy of Seinfeld or Friends. Also, she downplayed Hope’s name on her resume so as not to detract from the much-publicized launch of her soon-to-debut sitcom Suddenly Susan.

I wrote a letter to the Times — which they printed — pointing out that Brooke had been taught comedy by none other than Bob Hope over many years. My letter was never challenged. The episode was yet another example of the sometimes ephemeral quality of Hollywood friendships and loyalties.

__________________________________

Excerpted from THE LAUGH MAKERS: A Behind-the-Scenes Tribute to Bob Hope's Incredible Gag Writers (c) 2009 by Robert L. Mills and published by Bear Manor Media: . The book was chosen by Leonard Maltin as a “Top 20 Year-End Pick“ for 2009.

Order online at:

http://www.amazon.com/LAUGH-MAKERS-Behind-Scenes-Incredible/product-reviews/1593933231/ref=cm_cr_pr_link_2?ie=UTF8&showViewpoints=0&pageNumber=2